Fractured protons

|

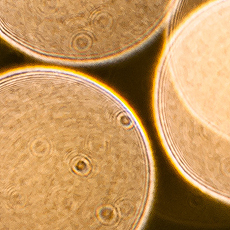

| Photograph of out-of-focus Christmas tree lights (large circles) that instead focuses on dust on the lens of the camera (small dark spots with rings). The rings around the dust are caused by diffraction. Photo: Jon Rista

|

In a bright light, you can sometimes see specks in your field of vision that resemble the picture above. If you try to turn your eyes to look at them, they move because these objects are sitting on your eyeball — blinking jostles them. They may be dust grains, cells or bubbles, but they are small enough to diffract light, making concentric rings like the ones shown in the picture.

Diffraction is a general phenomenon in which waves curl around small objects, with more or less intensity at different angles, like light around a dust grain. Protons in the LHC also diffract because protons are quantum mechanical waves. Sometimes protons simply bounce off each other, making ring-like patterns exactly like light bouncing off dust, but more often one or both of the protons break apart.

Diffraction in which one or both protons dissociate (break apart) is important to measure at LHC energies because it is a basic property of proton collisions that can't be calculated from first principles. In a recent paper, CMS scientists measured the probability of two protons diffracting with single dissociation (one breaks apart) and double dissociation (both break apart).

This measurement is unlike most performed at the LHC. Most LHC measurements involve a search for exceedingly rare phenomena, events that occur in one out of 10 trillion collisions, but diffractive events occur in about one out of four collisions. Instead of describing how individual particles decay, this analysis studies collective effects in the combined two-proton system.

One challenge of dealing with the combined system is the problem of determining which particles came from which proton when both protons break apart. In practice, physicists distinguish the two clouds of debris by looking for cases with a large angular separation between them relative to the beamline, but the available angular range is limited by the size of the CMS detector. This analysis used an additional detector, CASTOR, which extends the combined coverage all the way from 90 degrees to a 10th of a degree from the beamline.

Though weird, this study has far-reaching implications. By improving the world's knowledge of collective proton collision effects, these effects can be better simulated in predictions of nearly every other measurable at the LHC.

—Jim Pivarski

|

| These U.S. physicists contributed to this analysis. |

|

| These U.S. CMS students and postdocs have made a big impact on the commissioning of the CMS cathode strip chamber muon detector. From left: Jesse Heilman (UC Riverside), David Morse (Northeastern), Devin Taylor (Wisconsin), Christine McLean (UC Davis), Elizabeth Kennedy (UC Riverside), Senka Duric (Wisconsin), Justin Pilot (UC Davis), Hualin Mei (Florida), Wells Wulsin (Ohio State). Inset, from left: Pieter Everaerts (UCLA), Frank Golf (UC Santa Barbara). |

|