Origin of the smallest masses

|

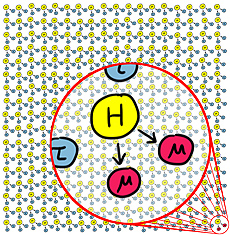

| Muons (red) are 18 times lighter than tau leptons (blue), so we expect Higgs decays to muon pairs to be about 300 times less common than Higgs decays to tau pairs. |

Since the discovery of the Higgs boson two years ago, about 80 analyses have helped to pin down its properties. Today, we know that it does not spin, that it is mirror-symmetric, and that it decays into pairs of W bosons, pairs of Z bosons, pairs of tau leptons, and pairs of photons (through a pair of short-lived top quarks). There are even weak hints at a fifth decay mode: decays into pairs of b quarks. All of these results are in agreement with expectations for a Standard Model Higgs boson, but they are still coarse measurements with significant uncertainties.

To say that this boson is a Standard Model Higgs is to say that it is exactly the particle that was predicted in 1964. That leaves a lot of room for surprises. Without interference from new phenomena, the rate that this boson decays into particle-antiparticle pairs would be proportional to the square of the mass of the particle-antiparticle pairs. The best way to check the proportionality of something is to look at it on an extreme range. Since the Higgs is believed to give mass to everything from 0.0005-GeV electrons to 173-GeV top quarks, there's plenty of room to check.

The highest decay rates are easiest to detect, so only the heaviest particle-antiparticle pairs have been tested so far. The lightest particle-antiparticle decay that has been observed is Higgs to pairs of tau leptons, which are 1.8 GeV each. The next-lighter final state that could be observed is Higgs to pairs of muons, which are 0.1 GeV each. By the expected scaling, Higgs to muon pairs should be 300 times less common. However, muons are easy to detect and clearly identify, so they make a good target.

Even if you combine all the LHC data collected so far, it would not be enough to see evidence of this decay mode. However, the LHC is scheduled to restart next spring at almost twice its former energy. Higher energy and more intense beams would produce more Higgs bosons, making a future detection of Higgs to muon pairs possible.

To prepare for such a discovery and find potential problems early, CMS scientists searched for Higgs to muon pairs in the current data set. They didn't find any, but they did establish that no more than 0.16 percent of Higgs bosons decay into muons, only a factor of 7 from the expected number, and then they used these results to project sensitivity in future LHC data. Incidentally, the Higgs boson is the first particle known to decay into tau lepton pairs much more (6.3 percent) than muon pairs (0.023 percent). All other particles decay into taus and muons almost equally.

They also searched for Higgs decays into electrons, the lighter cousin of muons and tau leptons. Since electrons are 200 times lighter than muons, Higgs to electron pairs is expected only 0.00000051 percent of the time. None were found, though an observation would been an exciting surprise!

—Jim Pivarski

|

| These physicists contributed to this analysis. |

|

| These scientists are the recipients of the 2015 Senior Distinguished Researcher Fellowship, awarded by the LHC Physics Center at Fermilab. The selection of these researchers was made by the LHC Physics Center management board. |

|