Spin!

|

| Spin is angular momentum, quantized into discrete units such as +1 and -1.

|

In the original Karate Kid movie, the kid who wants to learn karate is frustrated by his teacher's insistence that he spend his time painting fences and waxing cars. Only later is it revealed that the student had learned the fundamental moves without realizing it, blocking punches with "wax on, wax off." Similarly, the deepest mysteries of physics are taught in Physics 101, but they're hard to recognize in everyday objects like bicycle wheels and spinning tops.

One of these deep principles is the conservation of angular momentum. Angular momentum is the amount of rotation an object has, taking into account its mass and size, and it is curiously constant. A spinning figure skater has a constant angular momentum as she contracts her arms and twirls faster because a fast-spinning small object has as much angular momentum as a slow-spinning large object. A cloud of interstellar dust, stately drifting in a slow inward spiral, can eventually collapse into a pulsar the size of a city block, feverishly revolving around its axis a thousand times per second. The angular momentum stays the same.

Fundamental particles are infinitesimal points of zero size, so it's hard to imagine what it even means for them to rotate. We can, however, measure their angular momentum, and it seems to always come in discrete multiples of 1/2 like -1/2, 0, +1/2, +1, and nothing in between. This is a quantum mechanical effect, and each particle has an intrinsic or built-in angular momentum called spin. Particles of matter, such as electrons and quarks, all have spin 1/2 (called fermions), whereas particles of force or energy have integer spins: 0, 1, and 2 (called bosons). Photons, which are particles of light, can have spin -1 or +1, a phenomenon that is known to photographers as circular polarization.

|

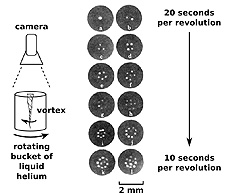

| Pictures of quantized vortices in liquid helium, photographed from above. (Yarmchuk, Gordon, and Packard, Observation of Stationary Vortex Arrays in Rotating Superfluid Helium, 1979). View more pictures of vortices in quantum fluids.

|

|

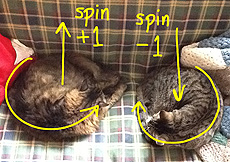

| Cats demonstrating same-spin photons, such as those from the decay of an excited graviton. |

Of all effects in quantum mechanics, the quantization of angular momentum was the hardest for me to accept because, for instance, we could simply put a particle on a record player and rotate it slowly, somewhere between 0 and 1/2, to try to defeat its all-or-nothingness. In fact, experiments like this have been done, not with single particles, but with buckets of quantum mechanical fluids such as liquid helium. This is the same fluid that was piped into the Tevatron to cool its magnets to superconducting temperatures. When liquid helium is rotated, it maintains a constant angular momentum by creating equal-sized vortices spinning the opposite way, in analogy with integer spins. These vortices are separate, discrete "units" of angular momentum, similar to how we think of spin. They even arrange themselves into regular patterns that precisely cancel the externally applied rotation (see side figure).

Spin has many applications. In 3-D movies, for instance, the left-eye and right-eye images are projected using spin -1 photons and spin +1 photons. The 3-D glasses filter out the appropriate spin for each eye. (It's a fortunate accident of biology that humans have as many eyes as photons have spin states.) Experimental new microchips use electron spins to store data, an emerging technology known as spintronics. Particle physicists use the spins of known particles to deduce the nature of new ones.

The new Higgs-like particle discovered this summer decays into two photons, and angular momentum must be conserved in that decay. If the new particle decays into opposite-spin photons, demonstrated by my cats in the top figure, then it must have had (+1) + (-1) = 0 spin, consistent with being a Higgs boson. If it decays into same-spin photons, then it must be a spin-2 particle, like a graviton. Scientists are currently struggling to measure that spin because it makes a big difference in how we interpret this discovery.

—Jim Pivarski

Want a phrase defined? Have a question? Email today@fnal.gov.

|